Welcome To My Blog

-

Get Rich or Die Tryin’

I’ve been a fan of 50 Cent since the first time I heard “In Da Club” as a teenager. The song’s an absolute banger, and seeing the music video where 50’s being operated on by Dr.Dre and Eminem (my favorite rapper) made me an instant fan. Of course, 50’s debut album “Get Rich Or Die… Read more

-

Gotham City

-

Cancel Culture

Anyone with a Social Media account has seen someone get “canceled.” Usually, it’s a public figure who gets caught doing something bad, resulting in hordes of angry people online. Initially, these vigilantes were fair and just (they only targeted the worst of the worst), but after they got a taste of their newfound power, a… Read more

-

The Hardest 10 Years

As we close out this decade, I’ve been reflecting on the past ten years of my life. Mainly how it went vs how I wished it did. In this blog post, I’m going to share a life-altering experience that shaped how 2010-2020 went for me.

-

My Experience with Drugs & Alcohol

I can vividly remember the first time I got high. I was a teenager hanging out at my friend’s house. My friend was an avid pot smoker and had an intriguing strain of weed called “God’s Gift.” We were looking for a place to smoke, and since my Mom and Stepdad were gone for the… Read more

-

Death & Regret

It’s always fascinating to watch the reaction to someone’s death. The instant news of a person’s demise hits, Social Media is flooded with tribute posts. Everyone writes long paragraphs professing how much they loved the person, how talented they were, and how sorely they’ll be missed. There are even cases of people becoming famous after… Read more

-

Growing Up As A Jehovah’s Witness

When you’re a kid, there’s nothing better than waking up early on Saturday and watching your favorite cartoons (Mine were Pokémon & Yu-Gi-Oh!). Instead of doing that, though, I would wake up at 5:30 AM, put on a suit, and get ready to spend the day knocking on doors. It’s safe to say my childhood… Read more

-

How Duke Valentino Killed The Generals Who Conspired Against Him

Excerpt from “The Essential Writings Of Machiavelli” “By the early 1500s, Cesare Borgia had become one of the most powerful men in Italy. Since his father had been elected to the pontificate in 1492 as Pope Alexander VI, Cesare Borgia had been made archbishop (at sixteen), cardinal (at seventeen), and finally Captain General of the… Read more

-

Standing Up For Yourself (A Lesson From Frederick Douglas)

I’ve let people walk all over me my entire life. I wasn’t born with one mean bone in my body, and I’ve always struggled with standing up for myself. Whether the disrespect was verbal or physical, I’ve constantly backed down in situations where I should’ve spoken up and let people know they were crossing my… Read more

-

Nobody Supports Me =/

When you start a new venture, you might be surprised at the lack of support you’re getting. It’s not uncommon to feel like your friends and family are ignoring your business & skipping the like button on your Social Media posts. It can naturally bring feelings of anger and disappointment. You may even find that… Read more

-

Romance At The Office

Let’s face the facts. At one point or another, we’ve all had a crush on someone at work. Whether it’s big butt Brenda or 6’4 Chad, who’s rumored to have a paid-off house and a 740 Credit Score. Chances are you’ve developed feelings or had a fling with someone in your professional life. There’s a… Read more

-

Nut House

One night, when I was a teenager, I got into a huge fight with my Aunt. My Dad overheard us arguing and joined our dispute. I said something smart to him and walked to my room. He followed me in, threw me against my bed, and started hitting me multiple times. I was pretty much… Read more

-

My Worst Three Jobs

Have you ever been lying in bed, dreading getting up and driving to a job you hate? I know I have, and today, I’m going to share my experience with three different jobs that had me feeling miserable. Job #1 – Nightmare Catalogs I was hired as a customer service representative for a catalog company.… Read more

-

Blood Money

It’s 5 AM, and my alarms going off. I pop out of bed and head to the kitchen, where I gobble down a granola bar and drink a glass of water. Now that I’m hydrated and have food in my system, I can start driving to my appointment. It’s time for my first of two… Read more

-

The Manipulated Man

Excerpt from “The Manipulated Man” by Esther Vilar breaking them in “To ensure that the happiness of man in subjugation is brought about by a woman and not by other men or some sort of animal, or even by one of the above-mentioned- social systems, a series of training exercises are built into man’s life,… Read more

-

No Respect For Success via Wickedness

Excerpt from “The Prince” by Niccolò Machiavelli Chapter VIII – Concerning those who have obtained a principality by Wickedness. “Although a prince may rise from a private station in two ways, neither of which can be entirely attributed to fortune or genius, yet it is manifest to me that I must not be silent on… Read more

-

The Gold & Silver Con Man (Jeffrey Ikahn)

The most cunning Snake of all time is the serpent Eve spoke to in the Garden of Eden. The second most cunning Snake is Jeffrey Ikahn. His nickname’s “The Wizard” cause he sells Gold & Silver and makes investors money disappear. This piece of shit is one of the shadiest human beings to ever come into existence.

-

Psychopath

Psychopath – A Snake with two legs that likes using cameras 🐍🎬

-

Burn Your Ships

Excerpt from “The 33 Strategies Of War” by Robert Greene Chapter 4 Create a sense of urgency and desperation – The Death-Ground Strategy You are your own worst enemy. You waste precious time dreaming of the future instead of engaging in the present. Since nothing seems urgent to you, you are only half involved in… Read more

-

Notes From Underground

Excerpt from Notes From Underground by Fydor Dostoyevsky “My schoolfellows met me with spiteful and merciless jibes because I was not like any of them. But I could not endure their taunts; I could not give in to them with the ignoble readiness with which they gave in to one another. I hated them from… Read more

-

PsYcHeDeLiC LiOn

-

How To Handle Defeat

“Defeat is bitter. Bitter to the common soldier, but trebly bitter to his general. The soldier may comfort himself with the thought that, whatever the result, he has done his duty faithfully and steadfastly, but the commander has failed in his duty if he has not won victory—for that is his duty. He has no… Read more

-

Leave The Past Behind

Always Remember – We can’t change the things that have already happened in life. What’s done is done. Stay locked in & focus on the greatness that lies ahead. The future is bright 😎

-

The Mindset Of A Capitalist

“Consequently, besides all the good things in life I want to give myself, I also want to increase my capital. How will I achieve this goal? Armed with this capital I propose to exploit you, and I propose that you permit me to exploit you. You will work and I will collect and appropriate and… Read more

-

Ecclesiastes

Ecclesiastes 1 Everything Is Meaningless 1) The words of the Teacher, son of David, king in Jerusalem: 2) “Meaningless! Meaningless!” says the Teacher. “Utterly meaningless! Everything is meaningless.” 3) What do people gain from all their labors at which they toil under the sun?4) Generations come and generations go, but the earth remains forever.5) The sun rises and the… Read more

-

Daniel in the Lion’s Den

Daniel 6 1) It pleased Darius to appoint 120 satraps to rule throughout the kingdom, 2) With three administrators over them, one of whom was Daniel. The satraps were made accountable to them so that the king might not suffer loss. 3) Now Daniel so distinguished himself among the administrators and the satraps by his exceptional qualities that the king… Read more

-

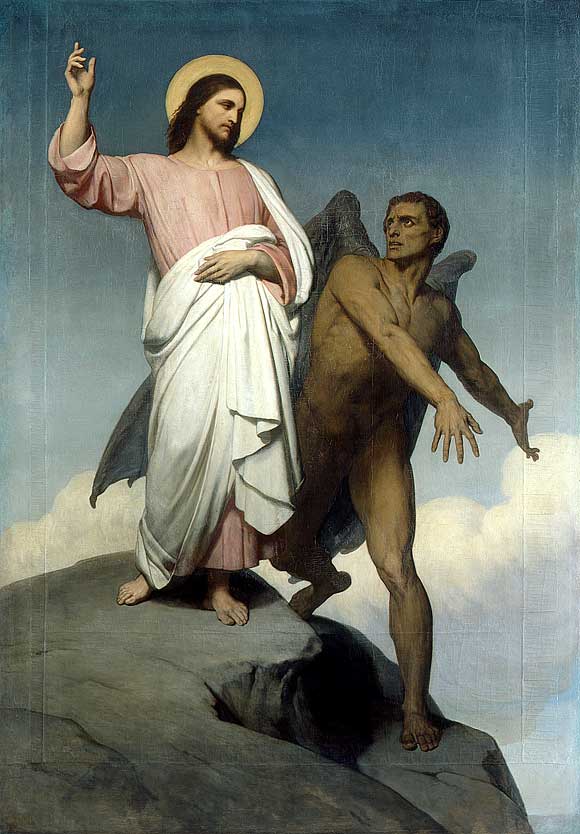

Jesus Refuses to Sell His Soul

Matthew 4 1) Then Jesus was led by the Spirit into the wilderness to be tempted by the devil. 2) After fasting forty days and forty nights, he was hungry. 3) The tempter came to him and said, “If you are the Son of God, tell these stones to become bread.” 4) Jesus answered, “It is written: ‘Man shall… Read more

-

Saul’s Growing Fear of David

1 Samuel:18 1) After David had finished talking with Saul, Jonathan became one in spirit with David, and he loved him as himself. 2) From that day Saul kept David with him and did not let him return home to his family. 3) And Jonathan made a covenant with David because he loved him as… Read more

-

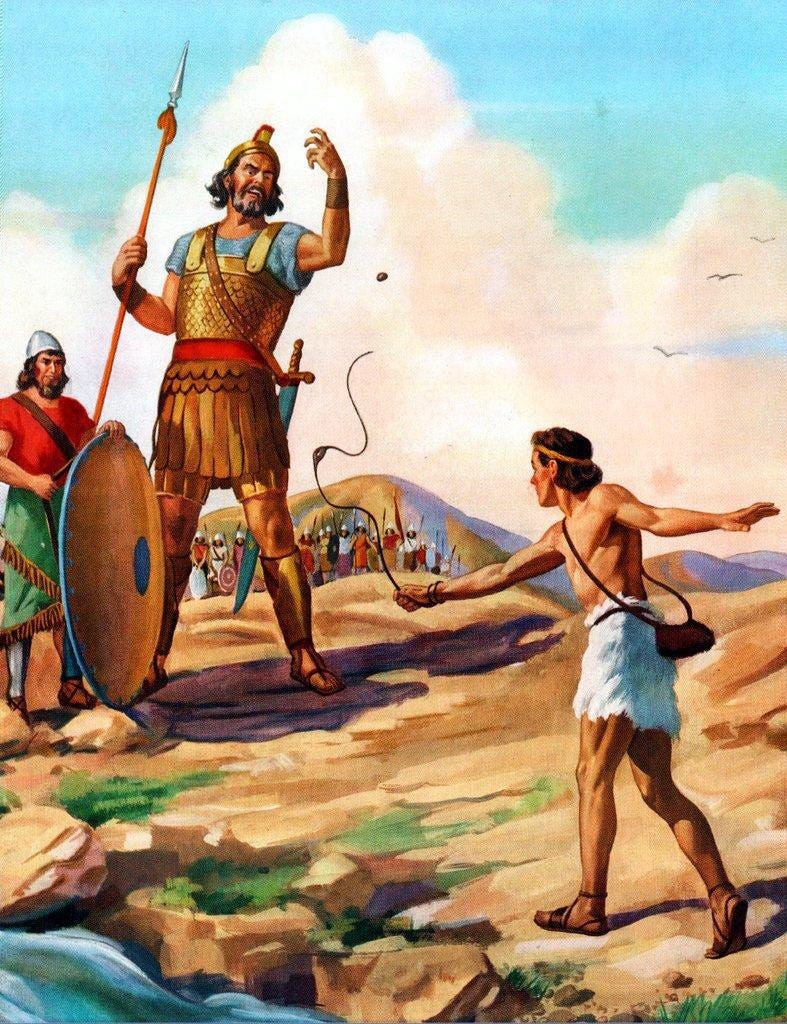

David and Goliath

1 Samuel 17 1) Now the Philistines gathered their forces for war and assembled at Sokoh in Judah. They pitched camp at Ephes Dammim, between Sokoh and Azekah. 2) Saul and the Israelites assembled and camped in the Valley of Elah and drew up their battle line to meet the Philistines. 3) The Philistines occupied… Read more

-

Temptations

Genesis Chapter 3 “Now the serpent was more cunning than any beast of the field which the Lord God had made. And he said to the woman, “Has God indeed said, ‘You shall not eat of every tree of the garden’?” And the woman said to the serpent, “We may eat the fruit of the trees of… Read more

-

Childhood Clue’s

This is a picture of me when I was a kid. Looking back at my Child Hood, I was obviously meant to be an artist. So much of my time was spent writing and reading books. As I got older, I quit engaging in those activities, though. Adult life and responsibilities took over, and I… Read more

-

Grandma’s Boy

Unfortunately, I was never able to develop a relationship with my biological mother. We didn’t have anything in common and could never get along with each other. Our relationship was terrible throughout my entire childhood. Thankfully the love I wasn’t able to find from my Mom I could get from my two grandmothers. As a… Read more

-

The Beginning

I’ve been thinking about writing for a while and decided to start a blog. I’ve been through a lot in my life, and I think this would be a good outlet to share some of the lessons I’ve learned throughout my journey. It also comforts me to know when I die my experiences will live… Read more

Follow My Blog

Get new content delivered directly to your inbox.